Bozoma Saint John on her biggest challenge yet: changing the way people feel about one of Silicon Valley’s most controversial companies

Please use the sharing tools found via the email icon at the top of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/0fefb486-da16-11e7-a039-c64b1c09b482

Share on Facebook (opens new window) Share on LinkedIn (opens new window) Save Save to myFT Leslie Hook in San Francisco DECEMBER 6, 2017 43 At a company full of challenging jobs, Bozoma Saint John surely has one of the toughest. As chief brand officer at Uber, her task is to try to get people to love a business that has become synonymous with the worst excesses of Silicon Valley culture. Earlier this year, a campaign urging users to #deleteUber went viral across the US, signalling how deep the public opprobrium runs — and how much work she has to do. Allegations of pervasive sexual harassment had surfaced by the time she accepted the job, and in the summer the company disciplined dozens of employees after conducting investigations. “I was aware of all the things that were happening here, but it didn’t deter me,” she says, in an interview at Uber’s headquarters in San Francisco. “I won’t lie to you and pretend like I’m not glad that some of this stuff is coming out of the dark . . . I wanted to join Uber because of those reasons. If we can’t prove that a culture can change, then we are doomed to say it is impossible.” Saint John was first introduced to Uber by board member Arianna Huffington, and met Travis Kalanick, then the company’s controversial chief executive, for an hours-long conversation at Huffington’s house in the spring. In the wake of the #deleteUber campaign in January, Kalanick realised the brand needed help, and decided that Saint John — who had already worked magic for Pepsi, Beats and Apple — could turn things around. Meeting her in person, it is easy to see why. Six feet tall and wearing a bright yellow dress, she has a charisma and optimism that is infectious; despite all the turbulence at Uber (Kalanick was ousted by investors in June, just weeks after she joined), she remains unflappably upbeat. “Companies can change. Culture can change. We have seen our society and our world change dramatically in the last 50 years, in terms of how people are treated, by their gender or by the colour of their skin,” she says.

Please use the sharing tools found via the email icon at the top of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/0fefb486-da16-11e7-a039-c64b1c09b482

Investors in Uber are surely hoping that she is right. The company has been through a period of unprecedented crisis this year, and Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber’s new chief executive, continues to face significant challenges, including hundreds of lawsuits and the threat of closure in a key market, London. Meanwhile, fraught negotiations over corporate governance have delayed a planned investment deal with SoftBank that could be worth between $7bn and $10bn. Against this backdrop, Uber’s damaged brand is a pressing issue. The company has lost nine percentage points of market share to its rival Lyft this year in the US — partly due to aggressive expansion from Lyft, which was long considered the underdog, and partly due to Uber’s dented image. I won’t lie to you and pretend like I’m not glad that some of this stuff is coming out of the dark Rebuilding that image is where Saint John comes in. Her role at Uber is the latest milestone in a marketing career that has often gravitated towards the entertainment industry, leveraging pop culture, sport and fashion to bring personality and wit into corporate brands that might otherwise have grown stale. Her ability to capture the zeitgeist was evident early on; while studying at Wesleyan College, she helped organise a number of campus parties, one featuring a young Jay Z. (“It wasn’t that well-attended but I was really excited. And now, of course, I can sit here and say, ‘I brought Jay Z to the campus,’” she told Cosmopolitan magazine.) After college, she worked for film director Spike Lee’s advertising agency SpikeDDB, and later moved to Pepsi, where she managed brands including Mountain Dew, Aquafina and Sierra Mist. In 2011 Saint John founded the music and entertainment division at Pepsi, where she brokered deals with music labels, artists and designers across the Pepsi brands, and even created a merchandising line of Pepsi T-shirts. “It was so much fun,” she remembers. A high point was leading Pepsi’s team for the Super Bowl campaign in 2013, when the drinks company sponsored the half-time show featuring Beyoncé — a performance watched by 100 million Americans.

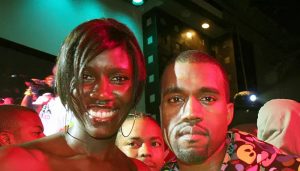

In 2014, following the death of her husband from cancer,

Saint John moved from New York to Los Angeles and started working with Jimmy Iovine and Dr Dre at the audio company Beats. When it was acquired by Apple a few months later, Saint John became head of global consumer marketing for Apple iTunes and Apple Music. Again, her team made waves with a viral ad campaign starring the singer Mary J Blige and actresses Kerry Washington and Taraji P Henson, in which the three women compare their favourite break-up-song playlists. Bozoma Saint John and Kanye West attend Pepsi Superstar DJ Contest in 2007 © Johnny Nunez/WireImage/Getty Images Saint John’s reputation as a rising star in Silicon Valley was cemented in June 2016, when she appeared onstage at Apple’s annual developer conference. Her presentation included leading the shy audience of programmers in a singalong to the Sugarhill Gang’s classic “Rapper’s Delight” on an iPhone, to show off Apple’s redesigned music service. (“Some of you guys are not rapping to the beat,” she chided the seated audience.) BuzzFeed promptly published a story: “Bozoma Saint John Is The Coolest Person To Ever Go Onstage At An Apple Event.” At Uber, her first big ad campaigns have featured tie-ups with the National Football League and the National Basketball Association. “Utilising these channels in pop culture is really important. People love the product [of Uber]; they don’t necessarily love the brand,” she admits. Uber has previously been seen as a utility, she explains, rather than a service that elicits an emotional connection with its users. “Pop culture . . . is a very effective way to add more, and to talk about the narrative,” she says. In Uber’s recent NBA campaign, sports journalist Cari Champion poses as an Uber driver, interviewing the young basketball stars he is ferrying around. Saint John is planning to take these sports-themed campaigns around the world. “You might do it in São Paulo and the football will be different but the idea will be the same. So I want to expand it.” Saint John was born in Connecticut, to Ghanaian parents, while her father was studying for a PhD in ethnomusicology and anthropology at Wesleyan University. She grew up moving frequently, including several years in Ghana and Kenya, before her family settled down in Colorado Springs when she was 12, and stayed there. We have seen our society and our world change dramatically in the last 50 years, in terms of how people are treated, by their gender or by the colour of their skin Growing up in Colorado, she became a student of pop culture as a way to survive. “For me, it wasn’t so much about blending in, because I just couldn’t, I mean it’s just not possible,” she says with a laugh, alluding to Colorado’s very white population. “For me, it was really about trying to understand how to better communicate with my classmates . . . it was trying to figure out just how to have conversations.” She devoured magazines, TV and radio programmes in her free time, as she looked for the right joke to make in the cafeteria or the right topic of conversation. She ran for student office many times, but never won. “That was what was so sad,” she says, with a rueful laugh. “But I think what that taught me was that I definitely was in it for my own reasons.” Today she speaks with an American accent, and says she considers herself bicultural. “I don’t know if I’m ever considered a part of the community I’m in. I think I’ve always felt an outsider, in both places, everywhere,” she reflects. In the US, people hear her name (pronounced “BOZE-ma”) and then ask where she is from. In Ghana, she says, everyone can tell from her accent and her walk that she is a foreigner. In Silicon Valley she is one of the very few black women in tech. When she joined Uber, she was the only black female executive, and the company reported earlier this year that just 9 per cent of its employees were black. Saint John explains that her desire to cultivate a more welcoming environment for people like herself was a big part of the reason she took the job. People love the Uber product. They don’t necessarily love the brand “I feel a real responsibility, about living in this day and being present,” she says. “If I can be in a position of power and influence, and be able to make my present better, then I want to do that.” Recently she joined the board of Girls Who Code in an effort to address the “pipeline issue” of the relative scarcity of women in computer science. “It’s also,” she continues, “about making sure that, not just this company but Silicon Valley, the industry, the larger corporate structures that we are in, are places that we can all thrive and feel equal and feel safe and feel happy, feel like we can contribute without any kind of friction — I want that utopia, and can I help create it? Of course.” In a year when many women — including former Uber engineer Susan Fowler — have come forward to speak about sexual harassment, Saint John says she welcomes the trend. “The political environment, especially now, has awakened a sense of pride and belonging for women across the country,” she says. “I think a lot of women have felt really powerless . . . and this feels like taking back the power. This feels like standing up and saying things that we didn’t say before.” She says she still draws on a lot of the same skills she developed in the middle-school cafeteria. “To be a black woman in this type of environment means that you are constantly looking for ways to connect to people,” she says. “When you are an outsider you don’t have that same foundation, so you have to work harder to communicate.”