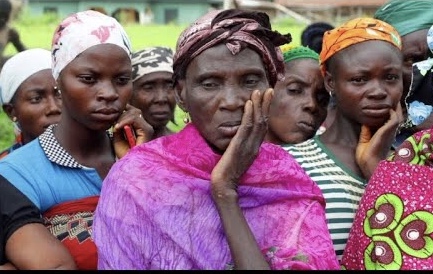

Across the Africa continent, the impact of marital death and divorce falls more heavily on women, who may be excluded socially and lose their homes and property after a marriage ends. One out of ten African women above the age of 14 is widowed, and six percent are divorced. Many more have been widowed or divorced at some point in their lives.

“In the face of divorce or widowhood, women often struggle with serious economic hardship,” said Asli Demirguc-Kunt, Director of Research at the World Bank. “Unfortunately, designing effective policies to prevent these women from falling into poverty is hamstrung by sparse data and research.”

At a recent Policy Research Talk on the issue, Dominique van de Walle, a Lead Economist at the World Bank, argued that providing widows and divorcees a secure foothold in society is central to the broader struggle for gender equality. In much of Africa, marriage is the sole basis for women’s access to social and economic rights, and these are lost upon divorce or widowhood.

Women frequently inherit nothing when a marriage ends, and official legal systems offer little recourse. Some may even lose their children to the husband’s lineage. Broader patterns of gender inequality add to the heavy burden on women’s shoulders. They are shut out of labor markets, have fewer productive assets, and bear greater responsibility for the care of children and the elderly.

Just as widows are often hidden from view in their own communities, the absence of data limits broader public awareness of the issue. Quantifying the prevalence of widowhood and divorce requires information on both current widows and divorcees as well as the marital history of currently married women, and this is only available in 20 countries.

The numbers show that brief marriages are a fact of life for many. Women tend to get married while young to much older men, and men are more likely to die in work-related accidents or in conflict. Many also succumb to HIV/AIDS. In addition, men who lose a spouse are much more likely to remarry than women, in part because of polygamy which is legal in 25 countries.

The options open to widows and divorcees after a marital dissolution vary greatly based on age, ethnicity, and social norms, but are often limited. In some regions, young widows are encouraged to remarry. Levirate marriage, a tradition in which a widow marries a relative of the deceased husband provides a modest safety net, but the remarried widow often occupies an inferior position in the new household.

In Senegal, for example, levirate marriage is associated with the lowest consumption levels for previously widowed women. These marriages can act as a poverty trap for those who cannot refuse due to a lack of means. In other settings, widows and divorcees may be shunned, ostracized, and dispossessed.

Divorcees and widows are also much more likely to suffer other forms of disadvantage. Relative to similar women in their first union, both groups have worse nutritional outcomes on average across Africa.

In Malawi widows are five times more likely than women who are married (and never widowed) to be HIV positive. Divorcees are not far behind.

“The prevalence of HIV varies enormously across marital status, with widows having the highest rates of HIV infection in most countries where we have data,” said van de Walle. “These women are doubly disadvantaged, and societies often do little to help them cope with this extraordinary challenge.”

The disadvantages that widows and divorcees suffer also affect their families.

Research in Mali shows that the children of widowed mothers have worse health and are less likely to be enrolled in school. However, in Zambia, in areas where customary rights do not support land inheritance for widows, married couples make fewer productive investments in their land. Where widows and divorcees suffer, society at large suffers as well.

“In many settings, working with the affected women solves one part of the problem,” said Bénédicte de la Brière, a Lead Economist at the World Bank. “But there also needs to be broader engagement with the community at large, and especially those in power.”

The right policy measures could shield widows and divorcees from the threat of poverty. Given the variety of countries, institutions, and legal systems covered in van de Walle’s research, no single policy formula applies across the board. Rather, policy makers will have to stitch together policies to fit their specific circumstances.

Policies that address systemic inequalities can enable women to support themselves in the face of a marital dissolution. These include reforms to credit markets, where women are particularly disadvantaged; ensuring equal ownership and inheritance rights for women; and securing customary marriages through registration and legal documentation.

Responsive policies can buoy widows and divorcees after a marriage ends. A widow’s pension can serve as a temporary safety net, as long as the benefits are transferred directly and securely to widows. Preferential access to housing and shelters is another measure that could help widows and divorcees in the event of a marital dissolution.

But, Van de Walle cautioned that research on the effectiveness of these policies is limited. The fate of widows and divorcees may depend on the willingness of African countries to invest in their most vulnerable people by evaluating whether these policy options notably improve the financial stability and social standing of their widows, divorcees, and their families.